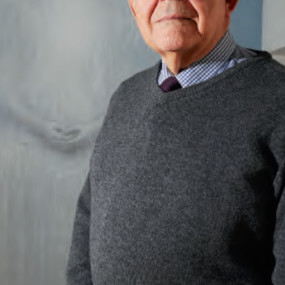

Guardian Of Waterperry

Approximately 25,000 people will descend on Waterperry House and gardens, on the outskirts of Oxford, next month for Art in Action. Here they will enjoy exhibitions, classes and performances from 400 artists, lecturers, and musicians – joined this year by the tent-makers of Cairo.

The event was the brainchild of artist, and steward of Waterperry gardens, Bernard Saunders who launched Art in Action in 1977. Bernard developed his lifelong interest in the arts as a child.

“My mother, Dora, encouraged me from a young age to travel to London with my brother to visit theatres and galleries,” he explained.

“On my first visit to the National Gallery, aged 11, I was attracted by a splash of vivid blue and, drawing near, I had my first sight of Leonardo da Vinci’s Madonna of the Rocks. I have learned since that blue is visually most intense when you are young.”

Bernard was born in Barnet in 1934, but his family were living in Southend when the Second World War broke out.

He vividly remembers, aged four-and-a-half. being evacuated. He and his older brother were among three coachloads of children being waved off by their parents.

“My brother Alan and I arrived in Derbyshire carrying our little bags and our gas masks and were billeted at a farm. I liked the place and the people but Alan, who was four years older than me, tended to court trouble and the family felt they could not look after us both,” Bernard said.

“We were separated, and I was sent to live with a mining family in Hartshorne, also in Derbyshire. My mother had nursing experience and, when she visited me, she recognised that the grandfather was suffering from tuberculosis – so I was moved again, this time to live with an arthritic old lady who had a beautiful garden. I spent a lot of time working in it, and have loved gardening ever since.”

Like all evacuees, Bernard had been sent away from danger, but ironically, it did not quite work out like that.

He said: “In November, 1940, we watched as a golden glow spread across the sky as Coventry burned – and then a couple of German bombers randomly discharged their bombs in the area, blowing up one house in Hartshorne.”

In 1944, Bernard and Alan returned home – they were now living in Bishop’s Stortford in Hertfordshire.

Bernard said: “My father, Horace, was a brilliant engineer, employed by a firm in the town to design a huge generator intended for Royal Navy minesweepers.

“It took me a while to settle down, and my relationship with my brother was volatile. My parents could only afford to send one of us to grammar school and that was Alan. I attended the local church primary school.

“My parents did not attend church but encouraged me to go and I became intensely religious. I loved singing in church.”

Then tragedy struck. “In 1946, when I was 12, my mother died of cancer. The cancer was in her marrowbone. She was in a great deal of pain but because nothing was visible, she struggled to convince people that she was not shirking. I tried to care for her and was alert to her suffering. I knew she had died even before they told me.

“My father Horace married again and his second wife, Jose, and I got on well – but Alan was not happy and left home as soon as he could. My father wanted him to be an engineer – but was disappointed when he became an art student.”

Alan graduated and went on to train teachers of art as well as practice it himself ( In contrast, Bernard’s schooldays ended at 15 when his father arranged an apprenticeship for him to train as an electrician.

A year later, in 1950, another traumatic event transformed the young man’s life – his father also died of cancer, aged just 47.

“When my father died, the owner of the factory where he had worked took me under his wing. I knew him as Mr Deerlove.”

Bernard experienced a change of fortune because the enlightened Mr Deerlove asked the16-year-old a life changing question:

“What do you really want to do?”

“I just did the apprenticeship for my father but really wanted to do something artistic,” Bernard recalled.

Mr Deerlove’s search for a suitable course was not easy because Bernard’ was due to do National Service.

“But he eventually fund a place at The City and Guilds of London and paid my fees and expenses,” said Bernard.

He commuted from Bishop’s Stortford as he was still living at home with Jose.

“I resolved to get out and Alan helped me to find accommodation in London. This was not the last time he helped – I loved him very much,” Bernard said.

“I loved art school and was quite good. Both the sculpture and etching teachers wanted me in their class. but I decided on sculpture.

“To get a National Diploma, I had to transfer to the Chelsea School of Art where I was a taught by Willi Soukop, Vivian Pitchforth Bernard Meadows and other well-known artists. My fees were paid but I needed to earn my keep so I took any work going – as a porter at Waterloo Station, and as a farm labourer.”

His National Service was deferred for a year so he could complete the course, but money was a problem. Then he found a night job as a telephonist in a block of serviced flats in Knightsbridge. “They left me a meal and also there was a camp bed I could use in the middle of the night.

“There was one particular tenant who often spent the small hours on the telephone to his girlfriend in Berlin and then I had to stay awake and still try to remain alert at college during the day. “But I completed the course. My thesis was on Tang art – so a piece from the British Museum is a possibility for my desert island.”

It was at this time Bernard met Verity, a student at St Martins School of Art. But just as they were getting to know each other, National Service looked as if it would play havoc with their lives.

Bernard was sent to a camp at Blandford Forum in Dorset for four weeks assessment. They told him he had an extraordinarily high IQ and should go for officer training.

Bernard said: “Considering that I had not had a good general education I was surprised, but in the army you do as you are told. I was sent to Honiton in Devon to join the Royal Engineers for pre-officer training, which was highly organised.

“I also became extremely fit and learned a lesson that has lasted all my life. There comes a moment of exhaustion, but if you struggle through that pain barrier you arrive at an inexhaustible energy reserve. I signed up for the parachute regiment and was all set to go when the Suez crisis put paid to it.”

In the meantime, Bernard’s personal life flourished. At Honiton, the officer recruits had weekends free, so he regularly hitch-hiked to London to visit Verity.

After National Service, he chose not to remain in the army but returned to the capital and moved in with Alan who was working at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Bernard said that, at first, Verity’s family were not keen about him marrying her. But they went ahead anyway and married in a register office.

Considering his earlier remarks about a passion for religion, I was surprised.

“By this time, I was no longer a believer but I had discovered philosophy.” he explained. “The School of Economic Science was founded during the Depression by an MP called Andrew Maclaren and his son Leon. It ran courses in economics,” Bernard explained.

“The courses were open to anyone and I began to attend every week. Its method of teaching was unusual. It developed a technique based on question and answer – the platonic tradition as finessed by the US Army. I eventually became a teacher at the school.”

With the help of Verity’s parents, the newly married couple acquired a rundown home in Barnes and Bernard had his first studio.

“To earn a living I worked for established sculptors. I would make fibre-glass casts and do carving, sometimes working on huge commissions.

“Another possibility for the desert island is the painting given to me by one of the artists. I worked for a volatile Frenchman called Claude Geoffroy Dechaume, who had a studio behind Kensington High Street. He was a fine silversmith and under him I learned to make jewellery – but he had difficulty looking after his finances. The School of Philosophy suggested they teach me some accountancy so I could help him – which I did.”

Bernard understands how hard it is to earn a living as an artist. “I had plenty of commissions for carving, but not of the kind I really wanted to do. I had commissions for carved picture frames, dolphin tables and eagles – but it often meant working all night for very little reward,” he said.

‘I discovered I had a talent for organisation and, sponsored by the school, set up a studio for 15 artists and craftsmen specialising in painting, sculpture, photography, silver-smithing, graphic design and illustration and fashion design.”

By 1971 Bernard and Verity had four children and it was then that he took a decision which put a strain on his marriage, which eventually led to divorce.

“The School of Economic Science approached three people, including me, about a position at Waterperry. They would provide free accommodation – though not spacious – and pay for my children’s education. I accepted the offer, but Verity wanted to stay in London, and moved here very reluctantly.

“It was doubly hard for her because, although I was steward of the 80-acre Waterperry estate, I continued to commute to London to work and run the studio. Verity eventually moved back to London with the children.”

“As we improved the estate, we began to open it to the public several times a year. It was seeing people visiting that gave me the inspiration for Art in Action. I thought it could be a vehicle to help artists connect and get work.

“The frrst Art in Action, in 1976, was small – just one marquee of demonstrators – but it showed work of 51 artists and craftsmen. We opened for three days over Whitsun and more than 14,000 people visited. Its success meant that we decided to repeat it the following year.

“I had asked an American friend, Kathy Watson, if she would help organise the show and it went from strength-to-strength.”

Nowadays, Art in Action attracts more than 24,000 visitors and and involves a huge variety of demonstrations and hands-on activities.

In 1978, Bernard began concentrating his efforts on developing Waterperry as an all-year-round attraction.

“The school is a charity and non-profit making. We developed the tearooms, the gallery and garden centre and began to employ up to 70 people in the summer – so we needed to form a limited company. Any profits from Waterperry Gardens go to the charity.”

“In 2005, after 28 years running Art in Action, I retired and Kathy retired at the same time. I am still steward ofWaterperry but I am no longer responsible for the day-to-day running.

“I am still actively involved in garden design and in the activities of the School of Economic Science – and I also organised the painting of the frescoes in the house.”

Bernard continues to live in Waterperry House with his second wife, Carolyn, who is currently learning Sanskrit.

They obviously have a shared interest as Bernard described how meditation became an important part of his life.

“In the mid-1960s, the school made contact with a leading figure of the Vedantic tradition in India, Maharaja Shri Shantananda Saraswati, from whom it received invaluable guidance in the study and practice of philosophy, for more than 30 years. I learned to meditate and it became the centre of my life,” he said.

Bernard showed me some well thumbed copies of the Upanishads and the Gita, Hindu philosophical texts.

“These would have to be candidates for the island. Philosophy and meditation open the door to the inner world of the spirit.

“I see a physical world and a subtle world of thought and feeling and intellect. It is difficult to go beyond that, but it makes a huge difference to life.

“Plato’s Republic was where my interest in philosophy began and memorable reads includes Tolstoy’s history of Peter the Great. I remember his description of St Petersburg – it was so beautiful.”

But what about his choice for our desert island? It was perhaps hardly surprising that Bernard, now 78, chose a sculpture for our desert island.

“I own very little and choosing art from the whole world is difficult – one possibility is the Madonna of the Rocks, but sculpture is important to me and I admire Rodin’s BurBhers of Calais. I would be happy with the copy that stands near the Houses of Parliament, but for me the most wonderful sculpture is Egyptian,” he said.

“The Ashmolean has a fine collection, but one of the colossal heads from The British Museum would look perfect on the island. They have incredible stillness.”

This article was first published in Oxfordshire Limited Edition, June 2012.