Simon Buchanan cuts a boyish figure considering the responsibilities he takes on. Recently appointed the steward of the Waterperry Estate as well as chief organiser of Art in Action, he is also a highly accomplished working sculptor. Still, his manner is light and in conversation he reveals himself as one who takes his work, but not himself too seriously.

He began his apprenticeship as a sculptor in the studio of Edwin Russell, a brilliant but intimidating figure working in the figurative tradition, whom he describes as “scary, tall, sinewy with massive eyebrows, like a great oak tree”. Simon starts by talking about the practical rather than the artistic side of sculpture. He tells me that when he started in a studio full of assistants, he spent most of his time doing up nuts and bolts under “big lumps of wood”. He talks about the “donkey-work”: the casting, making moulds, mixing of plaster and making armatures. As he elaborates the importance of getting an armature (the skeleton-like structure inside a sculpture) just right, I ask him if he always wanted to be a sculptor.

Simon explains that he grew up in an artistic family. His grandparents were accomplished painters, his father was an architect and his twin brother was involved in the arts, so initially he did not want to do the same thing. After doing science A levels, he went travelling and found himself sitting on the Great Wall of China sketching some bicycles, when the thought occurred to him that, “maybe I don’t have to do what everyone says I should do – I could just do what I love. Then I asked myself, what do I love? I looked down at my sketchbook and it came to me that all my life I had been drawing all over everything, walls, the back of my textbooks and it became absolutely clear to me what I was going to do.”

On his return to England, Simon met someone who was apprenticed to a well established sculptor. He invited him to join the workshop.

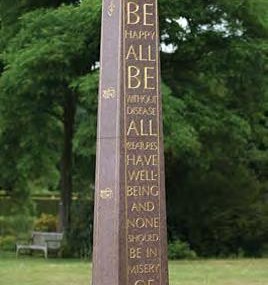

Simon’s work covers a wide gamut. From letter carving, to war memorials, from Victorian style angels to abstract sculptures, from obelisks to tiny animals. When asked about his enthusiasms and influences he says he began with an admiration for realism. He says as a young man he only really rated people who could “do figurative stuff”. Later he came to appreciate the more stylised twentieth century forms of Epstein and Eric Gill, but although he says it came slowly, Simon discovered that what he really loved were the anonymous medieval stone sculptors with their emphasis on human and animal forms. He talks about Chartres cathedral and the “symphony” of sculpture that makes up the frontage of this great medieval masterpiece. He stresses though that it is their stylised nature that appeals, the way they “catch the essence, without getting caught up in the outside form.”

Whilst this may sound a little esoteric, he does not indulge in any intellectual posturing. Discussing the work of some of the more abstract sculptors, Simon expresses respect for their skill, whilst disarmingly confessing that sometimes he just doesn’t “get it.” He adds, “I think we should all just trust our instincts. For me, the most attractive abstract art would be something like a nautilus shell, a beautiful seed or a particular part of a flower so exquisitely formed that it makes you believe in the watchmaker theory. The greatest abstract sculpture is out there in nature. I’ve yet to see any sculptures that compare with what is on our doorstep.”

This humility in the face of the natural world is reflected in his mode of work. He chooses to work on commission rather than produce pieces that have to be put on display for approval. In one way he says, this makes him “a gun for hire”, but he adds, “I enjoy the journey. They’re taking me to places I may never have gone before. Yes, I give the client what they want, but it is also my job to give them what they need. They may not know what that is, but it is my job to pick that up. I’ve deliberately decided to try to take my ego out of the equation and when I see it getting in the way, I’ll try and sidestep it and just work to serve the client.” This process occasionally produces a moment when he gets “a spark of inspiration and a sculpture or design will land fully formed in my head and I recognise it as not being part of the usual dross… the only job then, is to remain faithful to the original idea and not get side-tracked.”

Simon goes on to describe such a moment. “The most successful piece I have ever done was a toad… it seems to chime with people. I was in a studio when I was an apprentice working late one night and a toad came hopping in through the door. I picked it up and put it on the edge of a bucket and it just sat there in a certain way and I knew that that was a finished sculpture and I just did it. I modelled it on the spot – the size I saw it. That’s seeing what’s in front of you, but it can happen in a more internal way, a fully formed vision can turn up in your head –but that’s less common.” He goes on, “The best artists enable us to see the world as they see it. And if they connected in the present moment with what’s in front of them at the time they did it, and if they’re good, they take us into their present moment. They take us into now, which is where all happiness is.”

This preoccupation with service, lack of ego, reverence for nature makes more sense when seen in the context of his latest role as Steward of the Waterperry Estate and chief organiser of Art in Action, the annual international art festival which takes place at Waterperry Gardens attracting over 25,000 visitors over four days. The estate is owned by the School of Economic Science, a centre for spiritual and practical knowledge and enquiry.

I ask him about this new role. “I’ve followed in Bernard Saunders’ footsteps because he was a sculptor and also a member of the School of Economic Science as am I.” He continues, “The thing about Art in Action is that it is a unique art show where you can see the artists demonstrating. It’s not just about selling their work. The artists are selected as being at the top of their profession. You can come along and see someone give their full attention to whatever craft you are interested in. Usually they will be a master of their art and hopefully by watching them at work and by asking them questions you will get a real insight into whatever you love and you might even be inspired to go and work in the arts, as many people have.” It is clear that Simon celebrates other people’s creativity and is, he says, very happy to be doing that. “After all,” he adds, “Khalil Gibran says that work is love made visible”.

By Liz Tagert

This feature appears in the July/August 2015 issue of craft&design magazine. Copies of the magazine are available at The Gallery at Waterperry and also online at http://www.craftanddesign.net/magazine/240